Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

By Jessica Ordaz, special to CalMatters

This comment was originally posted by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

Guest Comment written by

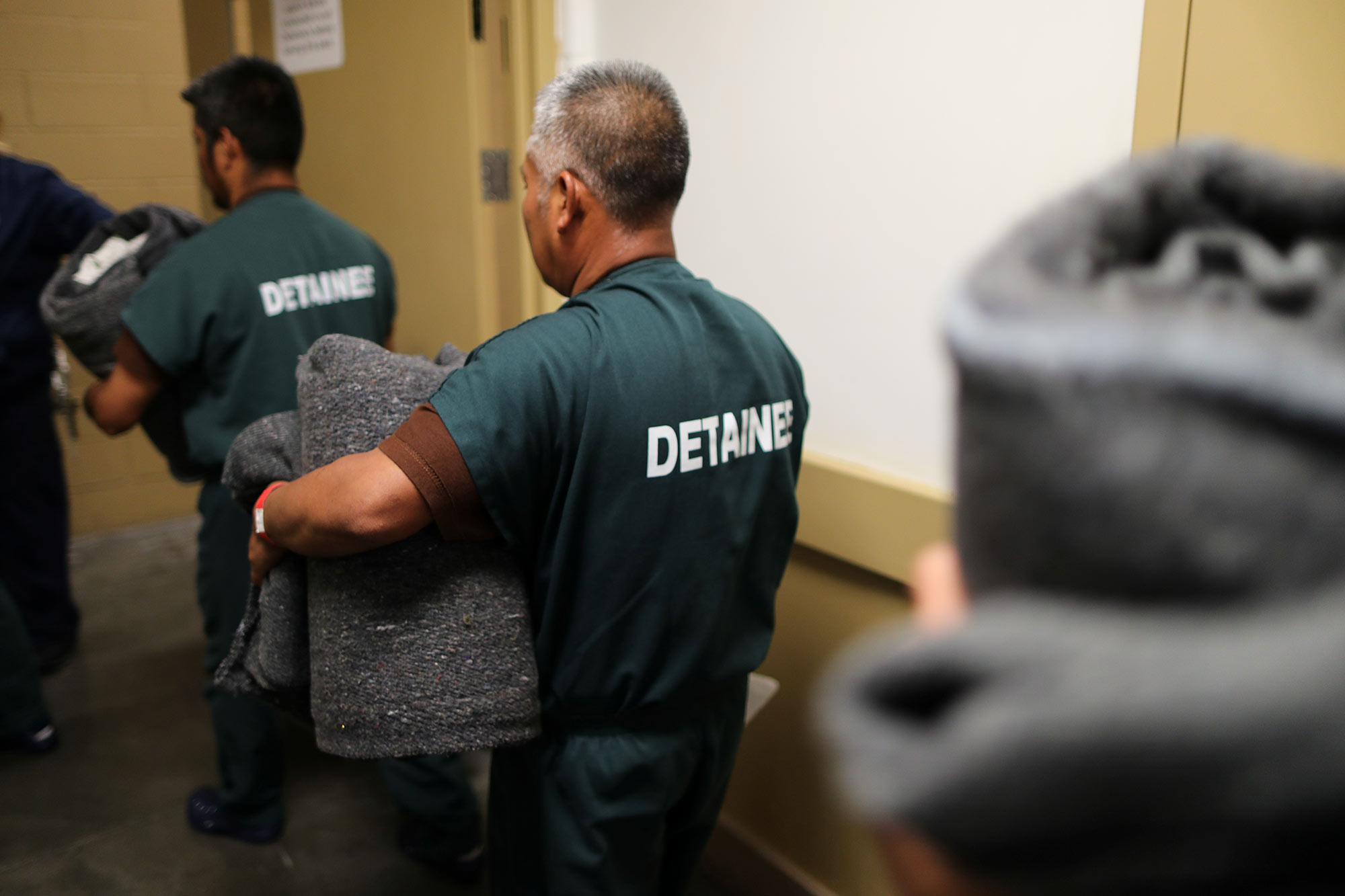

I keep thinking about Jose Rene Floresa Los Angeles resident incarcerated in a Southern California migrant detention center in the 1980s. The El Centro immigration detention center, where immigration agents sent Flores, has a long and deep history of brutality.

But Flores’ story is not all violence and abuse. It’s also a story of protest and solidarity—reflecting a larger line of resistance than domestic detention, including the people the Trump administration is currently working to silence and make disappear. They have risked their “lawless“lives in the hope that the world may learn of the inhumane conditions behind the prison walls and that they may be free.

Flores emigrated to the United States from El Salvador in 1980 after being attacked by members of his homeland’s National Guard, a paramilitary organization known for committing atrocities during the Salvadoran Civil War. As a teenager, he was noted for his participation in a factory union and for his involvement in revolutionary organization United Front for People’s Action.

“There was a terrible repression in El Salvador,” Flores told me when I interviewed him a few years ago. “I was criminalized because I had long hair and black glasses. Just looking different and being young meant you were a criminal, marihuanero, partisan and a junkie.”

When Flores arrived in Los Angeles, he was detained by Immigration and Naturalization Service officials who transported him to El Centro because he chose to apply for political asylum. The detention center, located in California’s Imperial Valley, was built to house unauthorized Mexicans and those convicted of deportable crimes in 1945. By the time Flores arrived there, it had grown from a small camp to a large-scale facility with a deep history of labor exploitation, physical abuse and surveillance.

INS officials forced Flores and his fellow migrant detainees to work as low-paid and sometimes unpaid laborers, limited their access to low-nutrient food and medical care, and controlled an atmosphere of physical and psychological intimidation.

Flores and several other Salvadoran migrants decided to fight back. We all felt the same, Flores said: “Insulted. Abused. We wanted to tell each other not to be sad. That we were all in this together.”

In 1981, they went on a 15-day hunger strike. Their refusal to eat and the use of their bodies for protest evoked the violence of the state by making society aware of the punitive nature of detention.

Thanks to the protest and the efforts of the immigrant support group Council ManzoThe INS released Flores from the facility that year.

Soon after, in 1985, a much larger hunger strike began in El Centro international news. Fifteen migrants from around the world organized an eight-day hunger strike. Between 175 and 300 imprisoned men participated, demanding that their grievances be heard.

While official INS accounts claim that the detention center functions simply as a place of administrative detention where people await their deportation hearings, the stories the strikers shared with lawyers and the media frame the detention center as a place of punishment.

The protesters also raised an important factor missing from the INS narrative: why many Central Americans migrated to the U.S. in the first place. A number of the protesters came because they were persecuted in their home countries for fighting against repressive Latin American regimes funded by US tax dollars.

The 1985 strike led to further crackdowns by INS officials. But it also helped shift the narrative around detention in the public eye, even as the U.S. continued to incarcerate immigrants and asylum seekers in facilities such as the Krome Services Processing Center in Florida, the Port Isabel Detention Center in Texas, and Guantanamo Bay in Cuba under both Democratic and Republican administrations.

The protests of people behind the walls of the detention center have never stopped. In the decades that followed, migrants demanded that lawyers and immigrant rights organizations hear and document their stories, filed class action lawsuitsand staged acts of disobedience, such as refusal to eat or work to provoke the cruelty of the state.

The dissent continues under “Trump’s reign of terror.” At the end of September, e.g. 19 imprisoned migrants have started a hunger strike at Louisiana’s Angolan prison, Camp J, calling for basic standards of care, such as prescription drugs, toilet paper and clean water.

Such acts of resistance and refusal from within show that despite the prison’s efforts to control, isolate and strip migrants of their humanity, people will continue to find ways to fight back.

This commentary is adapted from an essay written for Plinth Public Square.

This article was originally published on CalMatters and is republished under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives license.