Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

By Tama Brisbane, especially for CalMatters

This comment was originally posted by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

Guest Comment written by

I watched a new era in Stockton’s hip-hop scene come of age.

Moving to the city in the Central Valley in the early 2000s, I discovered a hip-hop community that was its own form of resistance. A smoldering frustration with the poverty, racial tension, and reputation for violence that has it he couldn’t shake it. Stockton’s sound was muffled more often than supported.

My adopted home carries a particular duality: burdened by perception and fueled by persistence. Hip-hop did not arrive here lightly. Heck, it wasn’t even invited—it rushed in.

One of the most enduring odds that Stockton hip-hop has struggled with is an identity crisis brought on by geography and distance, which hinders everything: access to the industry, audiences, and opportunities. We are 45 minutes from Sacramento and almost two hours from the bay, in the middle of a region that no one knows how to define. The bay has hyphae and an iconic ambassador in the E-40.

But Stockton? This in-between has never had a defining sound of its own.

But distant did not mean rejected. Back in the 1980s, Stockton was in the building. Thanks to legendary and local promoters like Hardin Fulcher, Brian Sampson, Thaddeus Smith and others, acts like Too Short, The Fat Boys, even NWA came out. And the Civic Auditorium was the people’s stage, the home of hip-hop before the city thought to make it truly welcoming.

Compare this with the venerable Bob Hope Theatrea downtown showpiece before the Stockton Arena was built. In an earlier era, black residents were forced to sit in the balcony, demonstrating how cultural exclusion was built into the city’s entertainment DNA.

Then in 2006, Stockton opened a $68 million arena, the official entry into the lucrative concert industry. The city had a chance to debut the venue with Carlos Santana — world famous, riding the wave of the mega-hit “Smooth” and culturally resonating with Stockton’s large Hispanic community. Instead, a white, aging, coolly popular Neil Diamond was cast, and paid $1 million— in front. The city announced a sold-out show, but backstage they gave out huge blocks of tickets to fill embarrassingly empty seats.

The end result: $400,000 in losses and a public outcry that cost the city manager his job.

At the same time of the city code enforcement the campaign targeted local promoters, nickel and diming them with exorbitant event permit fees, security and insurance – $100 if there was dancing, more for loud sound and a requirement to hire off-duty police as security.

How do you hip hop in silence and stillness? Taxes weren’t just unevenly applied—they were weaponized, used against genre and culture.

In 2005, when I was appointed to the Stockton Civil Grand Jury, one of our investigations highlighted the city’s discriminatory entertainment policies and heavy fees. When our report was published in 2006, the city was warned – and on the clock – to make changes. The official hip-hop door in Stockton was opening.

Enter Common: rapper, poet, activist. Thanks to the University of the Pacific’s music management program, in 2007 he became the first hip-hop artist to play at Hope. The sold-out show represents a seismic shift in the city’s entertainment landscape. And for weeks, one question echoed throughout the local hip-hop scene: Who’s opening the doors to Common?

I presented a local, collaborative showcase at the university. A Stockton-centric starter kit that reflects the range, artistry, and elevation possible—and profitable—for the hip-hop scene.

Hip-hop in Stockton didn’t just survive—it thrived. Local artists who once struggled to book a venue are now shaping the city’s vision of entertainment. In the person of Adonis Spiller, aka MadSpill, hip-hop is now on the Stockton Arts Commission, influencing both artistic funding and politics.

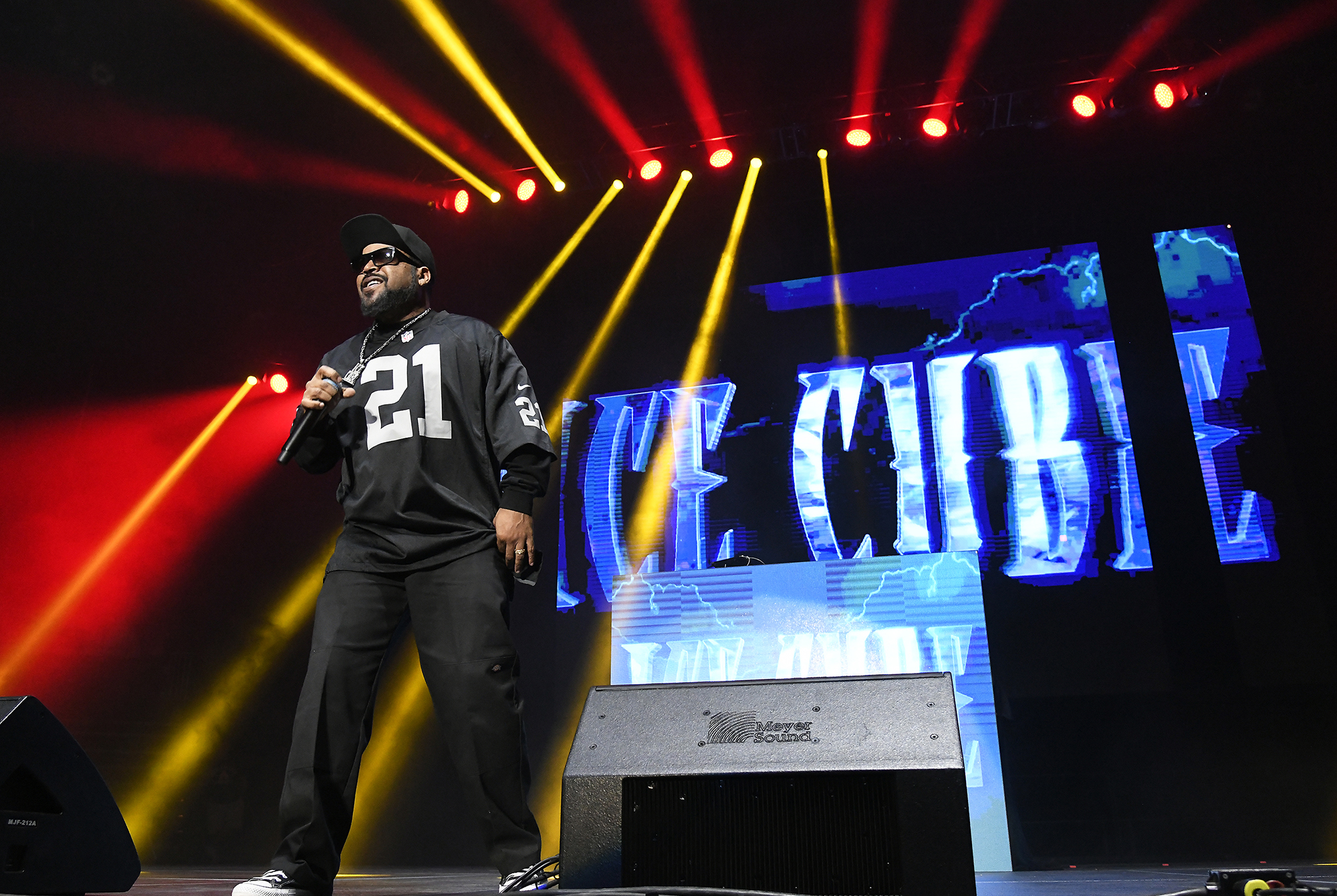

And the arena that once hosted Neil Diamond’s expensive debut/flop? It has since welcomed E-40, Lil Wayne and a parade of revenue-generating hip-hop artists. Stockton has yet to produce a breakout star, but the infrastructure, energy and community remain undeniable.

After all, Stockton hip-hop isn’t just about music or even about money. It’s about creating and displaying 209 stories. Stockton’s hip-hop scene was built not in spite of that city’s notorious violence, but often in direct response to it. 209 fights crime, systemic disinvestment, apathy, and oppression of its youth and communities of color—conditions that color the lyrics and experiences of its artists.

Artists like Daddex, MBNel, EBK Jaaybo, Holy, go ahead, Deozethat’s right, Surf baby, Braxie, Zeps, BLoveJones, Haiti Babii, Steve Spiffler and Mikaela Janae making waves in the region and beyond. that’s it Jazzmarie LatourStockton Poet Laureate, host of the city’s longest-running open mic, and Hatch Workshops, where hip-hop happens. It’s The Lyte, or standing-room-only event, where artists come to shine.

And one day the time will come, more or less, when Stockton Hip-Hop’s time will finally come.

This commentary is adapted from an essay created for Plinth Public Square.

This article was originally published on CalMatters and is republished under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives license.