Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Team of For the first time, geologists have discovered evidence that two ancient, continent-sized, superheated structures hidden underground formed the planet. The planet’s magnetic field Over the past 265 million years.

These two masses, known as Large Low Shear Velocity Provinces (LLSVPs), are part of the catalog of the most massive and mysterious objects on the planet. Current estimates indicate that each one is equivalent to the size of the African continent, although they are still buried at a depth of 2,900 kilometers.

Areas of low surface vertical velocity (LLVV) form irregular areas of the Earth’s mantle, and are not defined masses of rock or mineral as one might imagine. Inside, the mantle material is hotter, denser, and chemically different from the surrounding material. They’re also notable because there’s a “ring” of cold material surrounding them, where seismic waves travel faster.

Geologists had suspected the existence of these anomalies since the late 1970s, and were able to confirm them two decades later. After another 10 years of research, they now point to them directly as structures capable of modifying the Earth’s magnetic field.

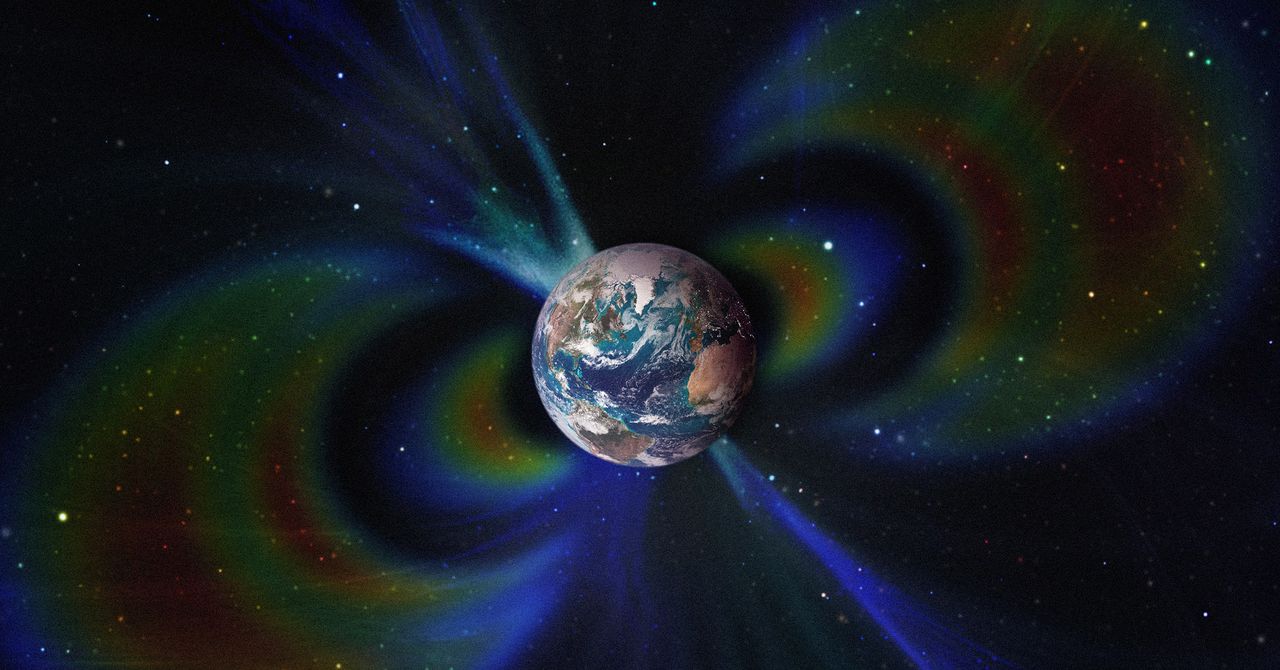

According to a study published this week in Natural Earth Sciences Led by researchers at the University of Liverpool, temperature differences between LLSVPs and the mantle material surrounding them change the way liquid iron flows in the core. This movement of iron is responsible for generating the Earth’s magnetic field.

Very hot and cold areas in the mantle together speed up or slow down the flow of liquid iron depending on the region, creating asymmetry. This discrepancy contributes to the magnetic field taking the irregular shape that we observe today.

The team analyzed available mantle evidence and ran simulations on supercomputers. They compared what the magnetic field should look like if the mantle were uniform, and how it behaved when it contained these heterogeneous regions with structures. They then compared both scenarios with real magnetic field data. Only the model including LLSVPs reproduced the same irregularities, inclinations and patterns that are currently observed.

Geodynamo simulations also revealed that some parts of the magnetic field have remained relatively stable for hundreds of millions of years, while other parts have changed significantly.

“These results also have important implications for questions surrounding ancient continental formations – such as the formation and breakup of Pangea – and may help resolve long-standing uncertainties in paleoclimate, paleobiology, and natural resource composition,” Andy Biggin, first author of the study and professor of terrestrial magnetism at the University of Liverpool, said at a press conference. He releases.

“These areas assumed that the Earth’s magnetic field, when averaged over long periods, behaves like a perfect bar magnet aligned with the planet’s rotation axis. Our findings are that this may not be entirely true,“ He added.

This story originally appeared on WIRED in Spanish It was translated from Spanish.