Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

From Marisa KendallCalmness

This story was originally published by CalmattersS Register about their ballots.

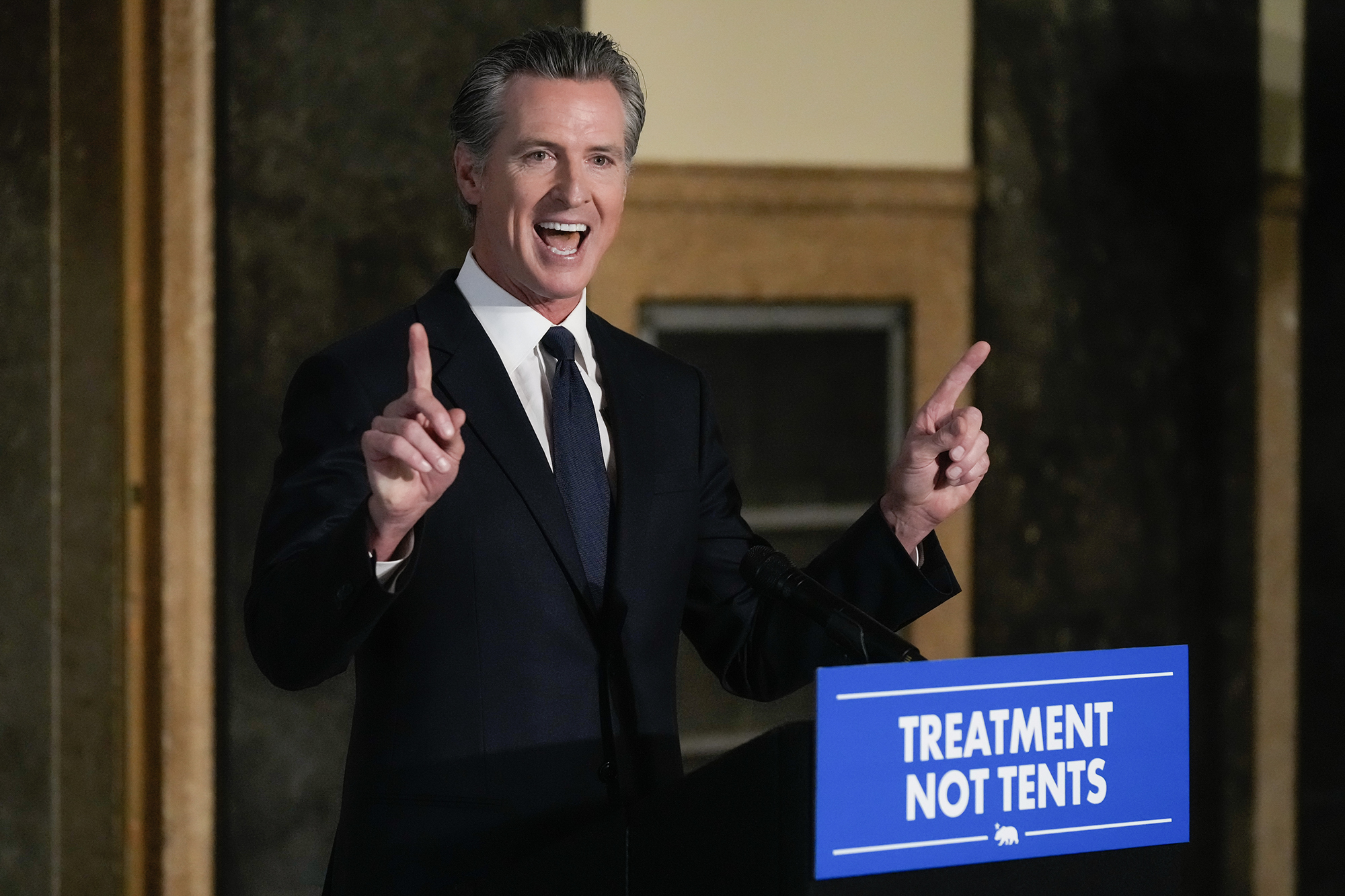

Gavin Newsom’s new governor The Mental Health Court has made great promises About how it would help to remove the most painful Californians from the streets.

Launched in 2023, the program allows people to bring a petition to the court to order treatment is for someone who is experiencing psychosis.

To see how the care courts have been working so far, Calfatters has asked data from every county in the state.

Here’s what we found:

Initially, the state estimated that 12,000 Californians could qualify for the program. Instead, only 2421 petitions were filed in July, according to the California Judicial Council. Only 528 of them have led to the fact that people care through voluntary treatment agreements or plans ordered in court.

San Diego County expected to receive 1,000 petitions in the first year and establish plans for the treatment of the court for 250 people. But in almost two years the county has received only 384 petitions and established 134 voluntary agreements. Los Angeles County saw 511 petitions submitted, with 112 led to agreements or care plans. In 2023, LA staff forecast news organizations that the county could enroll 4,500 people in the first year.

The sources we talked to have said it is in the end than expected to submit petitions. Counties believe that police, firefighters and other first responders will jump in the opportunity to bring petitions to the court on behalf of the sick, restless Californians who meet on the streets every day. But the overworked first responders did not have time to navigate in the process of taking time, said Amber Irvine, a coordinator of the behavioral health program of San Diego County.

In some cases, police and firefighters submitted petitions when the program first started. But they were often fired, which made them not tend to submit more, said Crystal Robbins, who managed a program to target a fire treatment in San Diego.

“We quickly realized that this is not a useful tool for the people we see,” she said.

About 45% of petitions have filed throughout the country, although this number includes a handful of cases in which someone has successfully “completed” the program. The odds are even higher in some cities, such as San Francisco, where nearly two-thirds of petitions were thrown away.

This can be for various reasons. Someone may not meet the narrow criteria to qualify for the care court. If the person is homeless, information workers may be difficult for them to find them. Or the person can simply refuse services. If so, Care Cart has few teeth to force them to comply.

The initial lure of the court of care for many supporters was the promise of treatment plans ordered by the court that would encourage sick people to accept the help they resisted. But most counties avoid this aspect of the program and instead provide treatment only if information workers can persuade someone to consider. The courts have ordered only 14 people on treatment plans, according to the Judicial Council.

Although these data show how many people are involved in the official care program, this does not count all people who have started the process and ultimately receive services through another district program instead, said Michel Doty Cabrera, CEO of the California Association of California Health Directors.

“I would say that I think the whole idea of looking at the numbers, it somehow misses the meaning,” she said.

One of the success of the court of care, she said, is the distribution of the word for the district services of people who may need them. As of December, people were diverted from the court of care and in other district services 1.358 times, according to a Recent report by the Health and Human Services Agency.

Currently, only people with schizophrenia and other limited psychotic disorders qualify. If Senator Thomas Humberg Senate Bill 27 Pass, the program will expand to include people who experience psychotic symptoms as a result of bipolar disorder.

It is not clear how much more cared for people, the court can reach the result. The Umberg service has no evaluation, and San Diego County says the bill can increase its number wherever 3.5% to 48.1%.

This is disturbing for people like Ervine. Adding many more people to the program will give clinicians a little time to spend with every customer, Irvine said. And Umberg’s account doesn’t come with money to hire more staff.

This article was Originally Published on CalMatters and was reissued under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Noderivatives License.